I recently compared .45 ACP and 10mm. Today I’m pitting .357 Magnum and .38 Special + P against one another!

Disclaimer

Ultimate Reloader LLC / Making with Metal Disclaimer: (by reading this article and/or watching video content you accept these terms). The content on this website (including videos, articles, ammunition reloading data, technical articles, gunsmithing and other information) is for demonstration purposes only. Do not attempt any of the processes or procedures shown or described on this website. All gunsmithing procedures should be carried out by a qualified and licensed gunsmith at their own risk. Do not attempt to repair or modify any firearms based on information on this website. Ultimate Reloader, LLC and Making With Metal can not be held liable for property or personal damage due to viewers/readers of this website performing activities, procedures, techniques, or practices described in whole or part on this website. By accepting these terms, you agree that you alone are solely responsible for your own safety and property as it pertains to activities, procedures, techniques, or practices described in whole or part on this website.

Revolvers for Self-Defense: A Brief History

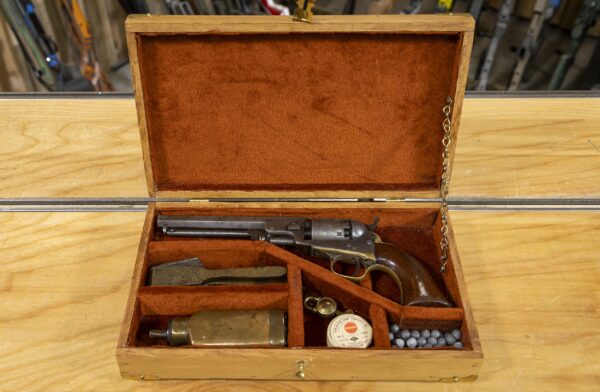

Traditional muzzleloading handguns came first, but things improved considerably with the advent of the revolver. Colt began producing percussion revolvers in the 1840s. By 1860, they had become well known and popular. Officers from both North and South wore revolvers during the Civil War. Many preferred the smaller Colt “pocket” revolver as it was small, lightweight and easy to carry — exactly the same reasons today’s carry guns tend to be small and lightweight.

The next big step was the introduction of metallic cartridges. This made the revolver much faster to load and improved reliability. The Army adopted the famous Colt Single Action Army and the .45 Colt cartridge in 1873. This sidearm quickly established a great reputation. Colt Single Action revolvers were sometimes referred to as “The Equalizer,” as the user was capable of defending himself/herself or protecting his/her family against larger, stronger opponents.

Double-action revolvers arrived on the scene surprisingly early and to this day are excellent for self-defense purposes. They offer the advantage of only needing the trigger to be pulled to operate, and are much faster to reload than a single action revolver.

Revolvers for Self-Defense: Considerations

I cannot overemphasize the importance of proper training! Not all firearms instructors today are well versed in the manual-of-arms for a double action revolver. It’s a skill that was once well-known, but has faded as so many enthusiasts and law enforcement agencies have turned to semi-automatic pistols for self-defense.

Several things should be considered when selecting a revolver for self-defense. The physical size of the revolver is of extreme importance. Revolvers range from quite small to monstrous. A small revolver is easier to conceal, but they can be difficult to shoot well. The short sight radius, small grip, and lack of weight all conspire to make accurate shooting difficult. Also many revolvers have only rudimentary sights, making accuracy difficult.

On the other hand, a particularly large revolver can be excessively heavy and bulky for concealed carry. The bigger guns typically offer a bigger, more comfortable grip, a longer sight radius, more weight to offset the recoil, and often much better sights. All that adds up to a gun that is easier to shoot well, as long as the power of the cartridge can be handled. If the handgun isn’t going to be concealed, then size is less important — for instance, if it’s a “nightstand gun” or kept at home or work for protection. Even a larger revolver can be concealed with a good holster and dressing appropriately. My personal revolvers range in size from a 23 ounce 3” barreled S&W Model 60 .357 magnum, to a 45 ounce 5” barreled S&W Model 629 .44 magnum. I have carried the 629 concealed under a vest or a jacket, but far more often I rely on a smaller, lighter revolver for concealed carry. It’s just easier.

How powerful should a revolver for self defense be? I urge people to use as powerful a revolver as they can handle well. For many people, a .38 Special or a .357 magnum is the choice. Fortunately a .357 magnum revolver can also use .38 Special ammunition, providing great versatility.

Consider your likely threat. If it’s an urban criminal, a modestly powerful and easily controlled cartridge such as the .38 Special is likely adequate. If aggressive, large animals like bears are anticipated, then a more powerful firearm with heavier bullets is a better choice. All things considered, the best “stopping power” is produced by excellent shot placement. Good hits from a modestly powerful handgun are much more effective than misses or poor hits from a very powerful handgun. This is especially critical with revolvers as they generally have smaller capacity than semi-automatic handguns. Regardless of what some say, revolvers are still pertinent for self defense. They’re simple to operate and often less intimidating for inexperienced shooters. They can be both powerful and accurate. The only real drawback to using a revolver for self defense is their typical five or six shot capacity and slower reload times (for most people).

History of the .38+P and .357 Magnum

Smith and Wesson’s .38 Special replaced the .38 Long Colt in 1902 and quickly became the standard firearm and cartridge combination for many law enforcement agencies across America. It remained the dominant law enforcement cartridge until the 1980s and 1990s when police forces switched to semi-automatic pistols.

Originally the .38 Special featured a 158 grain round nose lead bullet traveling at 755 to 800 fps. That easy-shooting version of the cartridge is still in production, but shooters quickly noticed the standard load was far from ideal for stopping aggressive outlaws. Efforts were made early on to improve it by changing bullet designs and by bumping up the power. By the 1930s, the .38/44 was available (the cartridge being what we’d consider to be the .38+P now). The .38/44 could be loaded to 20,000 psi rather than to 17,000 psi. It also sent 158 grain bullets at 890 fps and 125 grain bullets at 945 fps.

None other than Elmer Keith was working towards improving the .38 Special for hunting, loading it to higher pressures and velocities. Phil Sharpe, a gun writer at the time, also believed that the .38 could be loaded to considerably higher pressures. Their work impressed Smith and Wesson, resulting in the introduction of the .357 S&W Magnum cartridge in 1935.

The 35,00 psi .357 Magnum MAP (maximum average pressure) is literally double that of the original .38 Special! To prevent the high pressure magnum cartridge from being chambered in a weaker, older .38 Special revolver, the case was lengthened .135”, which should prevent that.

The cartridge quickly garnered a great deal of respect. The first S&W .357 magnums were expensive and built on the large N-frame S&W revolver which was also used for the .44’s and .45’s. J. Edgar Hoover, head of the FBI, received the very first S&W .357 magnum revolver.

General George Patton is often pictured with his ivory gripped revolvers in WWII photos. (Ivory, not pearl!)

One of them was a Smith and Wesson .357 magnum that he received in 1935. Production ceased from 1941-1948 as weapons production focused on supplying the military during WWII.

Patton said of the grips: “They’re ivory. Only a pimp from a cheap New Orleans whorehouse would carry a pearl-handled pistol.”

By the 1950s post-WWII economy, more private citizens were able to afford the S&W revolvers and law enforcement use of the powerful cartridge increased. Another giant, literally, who had a lot to do with the .357 magnum was legendary WWII veteran and Border Patrol officer, Bill Jordan. Jordan stood 6 ½ feet tall and had large hands. The “Jordan Trooper” grips were made large to accommodate his paws. Jordan was extremely fast with his revolvers and rather experienced with gunfighting. At his urging, Smith and Wesson chambered their smaller K-frame revolver for the powerful .357 magnum cartridge and came out with what was called the Combat Magnum in 1955. That became the Model 19, and later, the stainless steel version, the Model 66. At one time, the Navy SEAL teams had the Model 66 in their inventory. They believed that after being submerged in salt water it still provided a reliable means of delivering a disabling blow to any opponent. It’s also well worth noting that the 125 grain .357 magnum factory load established an extremely impressive record of successful “stops” by law enforcement officers.

Ballistics

Each of these cartridges are traditional for self defense use in revolvers.

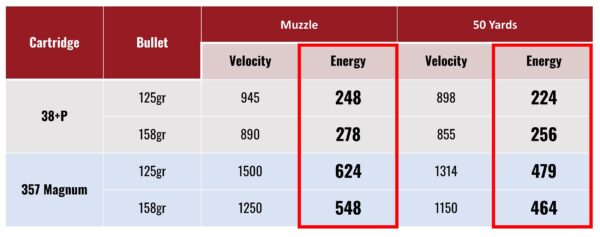

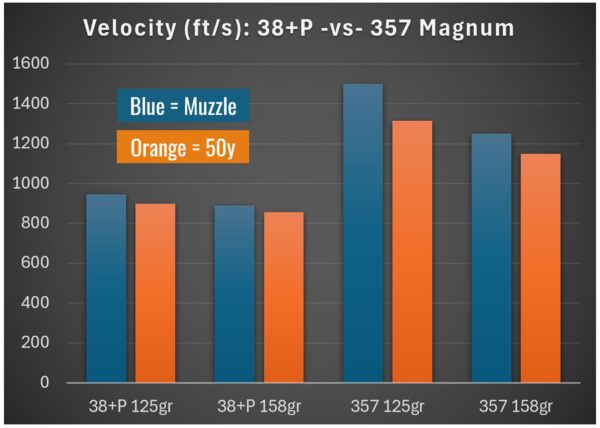

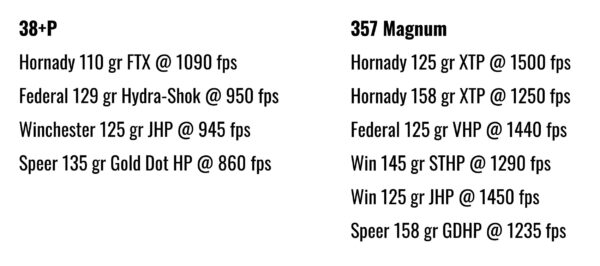

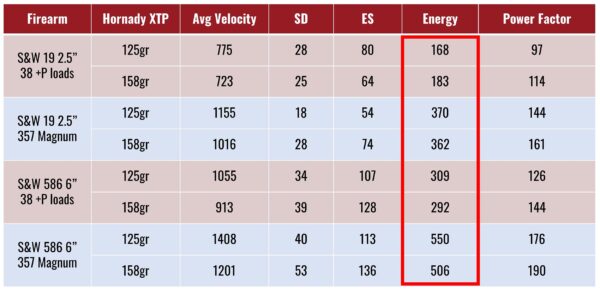

These ballistics were taken from .38+P and .357 Magnum commercial ammunition. I also wanted to sample a light bullet load and a heavy bullet load for each caliber.

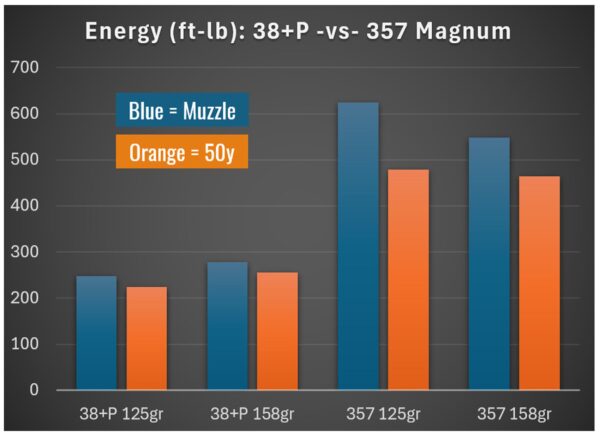

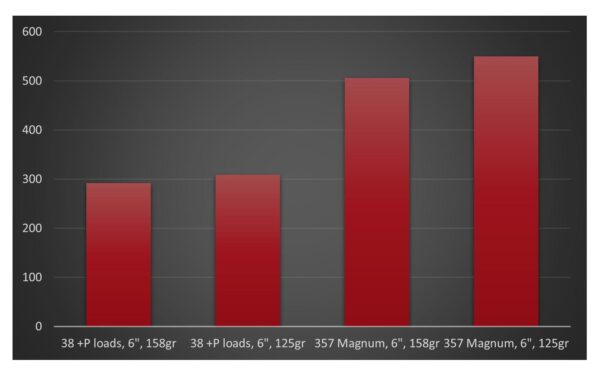

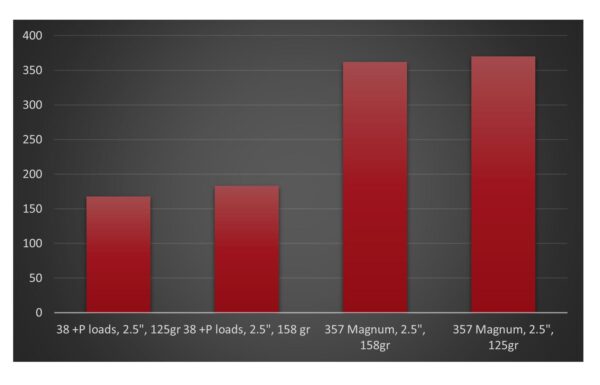

The velocity differences are impressive, but only start the tale. For a defensive handgun, I think a more compelling figure is the ft.-lbs. of energy developed by each.

Energy is a useful tool for comparing cartridges. It’s notable that even at 50 yards, both types of .357 magnum ammunition are still far more powerful than either of the .38+P loads at the muzzle!

Common Self-Defense .38+P and .357 Magnum Ammo Types

All of the major ammunition manufacturers offer at least a few types of ammunition in both .38 and .357. Going through our local gun shops, I noted a fair selection and quantity of .38 Special practice/range ammo available, but far less of the more expensive self defense .38+P and .357 Magnum rounds.

Costs

Both .38+P and .357 Magnum can be expensive to shoot! .38+P factory ammo runs between $1.10 and $1.32 per round while .357 Magnum ranges from $1.05 to a mind boggling $2.00 per round! Self-defense handgun ammo is expensive to produce, which is reflected in the pricing. Factory self-defense ammo often features nickel-plated cases, sealed primers, special flash-reducing powders, and an advanced bullet design intended to do well in FBI testing protocols. All that costs money. This is why so much self-defense ammunition is offered only in 20-round boxes.

As shooters, we have a couple ways to beat those high costs for our practice ammo. We can buy less expensive practice ammunition in bulk, seriously undercutting the price of the premium self-defense ammo, or we can handload.

If I include the cost of the brass cartridge cases, my handloads for all four types I assembled averaged about $0.50 cents each. The brass case can be reloaded many times so it becomes much cheaper to load and shoot with reuse. I’ve lost count of how many times I’ve reloaded some of my old .38 Special cases.

Some people object that “time is money” and figure in that cost per hour. I enjoy loading my own ammunition— it’s part of my shooting hobby and always has been. By loading my own ammunition, I also feel I get to know its characteristics better. So for me, there’s no real cost in the time spent handloading—it’s just pleasure for me.

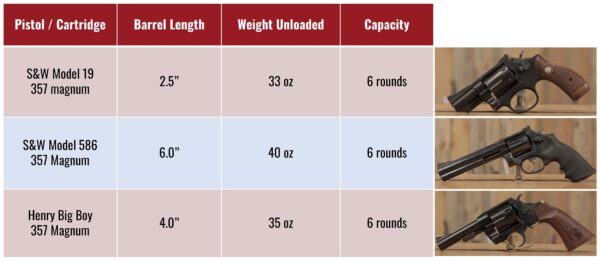

About the Revolvers

For our velocity testing we used a 2.5” Smith and Wesson Model 19 and a 6” Smith and Wesson 586. We also shot the newish 4.0” Henry Big Boy revolver. All three are well made, reliable and accurate revolvers, although the Model 19 is starting to show its age after a lot of use over the years.

About the Loads

A note about the use of handloads for self defense: it’s a controversial subject. Some argue that assembling your own handloads puts an individual at greater risk in both criminal and civil trials after a shooting. Even in a justified shooting, a civil suit is likely. Others say that the use of handloads poses no legal risks. It pays to research the subject and make your own decision. I prefer to use factory loads for my carry guns, in part because of the low-flash additives to the powder used by many manufacturers. Commercial self-defense ammo is held to high standards, but there can be ammo failures even with ostensibly high-quality commercial ammunition.

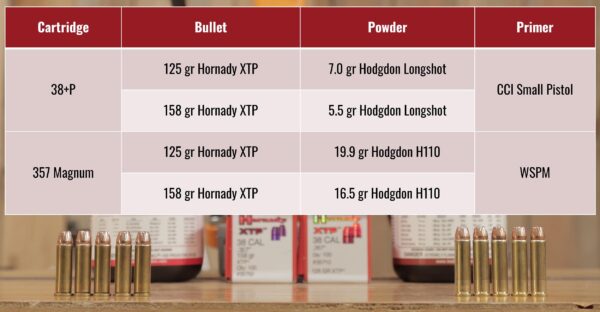

Also note that these loads are at or near MAXIMUM. The data came from Hodgdon’s Reloading Data Center. The .38+P loads are at the top for each bullet weight as are both .357 Magnum loads. Please work up carefully to the level where you are comfortable and safe and do not exceed published load data.

Hornady’s XTP bullet became available over 30 years ago and has earned a great reputation as a self-defense bullet and also for hunting medium game. I chose to use XTP bullets across the board for this comparison. I loaded all ammunition using RCBS carbide dies on a Lyman Brass Smith All-American 8 turret press. For my own revolver practice, I often use handloaded .38 Special or .357 Magnum ammunition at less than 1,000 fps with less expensive plated or cast bullets.

Both are economical loads that also take it easy on both the gun and the shooter. Using the shorter .38 Special ammunition can result in “crud rings” developing inside the chambers of the long .357 Magnum cylinders. To avoid that, many handloaders assemble mild handloads in .357 Magnum cases. I’ll shoot some full strength .357’s from time to time to retain familiarity with controlling them for rapid and accurate shooting.

I used Hodgdon’s Longshot powder for the .38 + P loads. Longshot is an interesting powder, and is used in shotshells as well as in handgun cartridges. I found that it measures easily and accurately from a manually-operated powder measure, making it ideal for use with a progressive press. I’m looking forward to trying it in other handgun cartridges soon. Hodgdon’s data did not supply a starting load, only the maximum load: 7.0 grains for the 125 grain Hornady XTP and 5.5 grains for the 158 grain XTP. *Hodgdon’s data is from a 7.7” barrel. We used 2.5” and 6” 357 Magnum barreled revolvers and I anticipated seeing lower velocities than what’s been published (1,228 fps for 125 grain and 965 fps for 158 grain).

I used a powder I am very familiar with for the .357 Magnum loads —Hodgdon H110. I’ve used it for years in the .357 Magnum, .44 Magnum, and .500 S&W Magnum. It’s a very fine grained spherical powder that flows smoothly through a powder measure for accurate charges.

Hodgdon’s .357 Magnum Loads can also be found in their Reloading Data Center. Hodgdon used a 10” test barrel — I immediately knew our 2.5” and 6” barreled revolvers would not match the velocities achieved with that long test barrel. Not only did our revolvers have shorter barrels, but by design have a barrel-cylinder gap which bleeds off some of the expanding gasses produced by the burning smokeless powder. Hodgdon recommended a starting load of 21.0 grains of H110 with a 125 grain XTP and a maximum load of 22.0 grains. The starting load was 15.0 grains with a 158 grain XTP with a maximum load of 16.7 grains. As always, it was a pleasure using H110. Not only does it flow beautifully through the manual powder measure, but it fills the .357 magnum cartridge case nearly completely. This prevents inadvertent double-charging and contributes to tighter velocity spreads for lower SD and ES figures, which typically results in excellent accuracy. The Standard Deviation and Extreme Spread figures for the 125 grain load were particularly tight from my old 2.5” Smith and Wesson Model 19 revolver.

Results

The .38+P loads from a 6” revolver nearly matched the velocity and energy produced by the .357 Magnum loads fired from the short 2.5” barrel.

Barrel length has a big influence on the velocity achieved by revolver cartridges. As anticipated, the .357 Magnum 125 grain XTP produced just over 1400 fps from the 6” revolver and was our fastest handload.

It also produced the highest energy figure at an impressive 550 ft.-lbs. The 158 grain .357 Magnum load managed 1201 fps from the 6” revolver, within 50 fps of commercial loads advertised at 1250 fps, but far short of the nearly 1600 fps obtained by Hodgdon from their 10” test barrel.

Shooting Impressions

These impressions are of both the cartridges and of the revolvers themselves.

Smith and Wesson developed the stronger, heavier Model 586 and 686 revolvers in part because of problems with the older and more lightly built Model 19. These issues arose from firing a large quantity of high pressure .357 magnum ammunition. The Model 586 and 686 revolvers were intended from the start to handle a steady diet of magnum ammunition.

I’ve carried and shot my old Model 19 quite a bit over the years and am accustomed to the recoil level. The recoil is brisk but controllable.

The factory grips are great for concealment and are fine when shooting .38+P ammunition, but leave something to be desired when using .357 magnums. I’d appreciate a bigger, more hand-filling grip for that. The short-barreled Model 19 handles quickly and easily. I’m able to draw it from the Galco concealment holster fast and get on target quickly.

In contrast, the heavier and longer Model 586 is a little slower-handling, but hangs on target better and better reduced recoil which helped me recover faster between rapid fire shots.

The comfortable rubber grips also lessen the felt recoil. Even the strongest .357 loads were easy to deal with when shooting the Model 586.

Head-to-Head

Head to head. Pros and cons… The .357 Magnum is obviously the more powerful of the two cartridges with higher velocity and higher energy figures. It does appear to be the better choice against aggressive four-legged wildlife, particularly with heavy bullets.

However, the .357 Magnum is indeed more difficult to control, but not at all unmanageable from a full size revolver like the 586 and 686 or the Ruger GP-100.

The .38+P continues to be a favorite of those who prefer the lighter recoil and quicker shot-to-shot recovery. With lower velocity and energy, it’s likely to penetrate less than its magnum counterpart, potentially making it safer for use in urban areas. The only real drawback to the .38+P is simply that it lacks the power of the .357 Magnum.

Conclusion

.357 Magnum and .38 Special remain the most popular revolver cartridges for self-defense for good reasons. They’ve been available for so long that ammunition has been refined and improved and is usually readily available. The .38+P is good for self-defense, and the .357 Magnum is a more powerful alternative. The .357, particularly with the high velocity 125 grain jacketed hollow point ammunition, has established a great reputation for quickly stopping attackers.

Fortunately the owner of a .357 Magnum revolver can choose between either cartridge, in many different bullet weights and configurations to meet different requirements.

I often carry .38+P ammunition in town and switch to high-powered .357 Magnum ammunition when I’m camping, fishing, hiking, or hunting in bear country. Here in my home state of Washington, we have wolves, black bears, and mountain lions that all present a possible threat, although I am more concerned about potentially having to deal with an aggressive human attacker.

Get the Gear

Hornady .38 Special 125 Grain XTP American Gunner Ammunition at Midsouth Shooters Supply

Hornady .38 Special 158 Grain XTP Hollow Point Ammunition at Midsouth Shooters Supply

Hornady .357 Mag 125 Grain XTP American Gunner Ammunition at Midsouth Shooters Supply

Hornady .357 Mag 158 Grain XTP Jacketed Hollow Point Ammunition at Midsouth Shooters Supply

Hornady .38 Special Unprimed Pistol Brass at Midsouth Shooters Supply

Hornady .357 Mag Unprimed Brass at Midsouth Shooters Supply

CCI #500 Primers at Midsouth Shooters Supply

Winchester Small Pistol Magnum Primers at Midsouth Shooters Supply

Hodgdon Longshot Smokeless Powder at Midsouth Shooters Supply

Hodgdon H110 Smokeless Pistol Powder at Midsouth Shooters Supply

RCBS .38 Special/.357 Mag Carbide Roll Crimp 3 Die Set at Midsouth Shooters Supply and RCBS

3 Die Set Including Carbide Sizer Die Expander | RCBS

Lyman Brass Smith All-American 8-Station Turret Press Reloading Kit at Midsouth Shooters Supply

Don’t miss out on Ultimate Reloader updates, make sure you’re subscribed!

Thanks,

Guy Miner