One of my favorite things about SHOT Show is the opportunity to sit down and talk with Bryan Litz of Applied Ballistics. This year’s discussion was incredibly insightful and deep – watch the full video for Bryan’s latest research on rimfire!

Disclaimer

Ultimate Reloader LLC / Making with Metal Disclaimer: (by reading this article and/or watching video content you accept these terms). The content on this website (including videos, articles, ammunition reloading data, technical articles, gunsmithing and other information) is for demonstration purposes only. Do not attempt any of the processes or procedures shown or described on this website. All gunsmithing procedures should be carried out by a qualified and licensed gunsmith at their own risk. Do not attempt to repair or modify any firearms based on information on this website. Ultimate Reloader, LLC and Making With Metal can not be held liable for property or personal damage due to viewers/readers of this website performing activities, procedures, techniques, or practices described in whole or part on this website. By accepting these terms, you agree that you alone are solely responsible for your own safety and property as it pertains to activities, procedures, techniques, or practices described in whole or part on this website.

About Applied Ballistics

Bryan Litz, founder of Applied Ballistics and Chief Ballistician for Berger Bullets, is a world renowned expert in long range shooting, data, and ballistics.

From Applied Ballistics:

Applied Ballistics’ mission is to be a complete and unbiased source of external ballistics information for long range shooters. We’re highly active in R&D, constantly testing new claims, products and ideas for potential merit and dispensing with the marketing hype which can make it so difficult for shooters to master the challenging discipline of long range shooting. We believe in the scientific method and promote mastery thru understanding of the fundamentals. Our work is passed on to the shooting community in the form of instructional materials which are easy to understand, and products such as ballistic software which runs on many platforms. If you’re a long range shooter who’s eager to learn about the science of your craft, we’re here for you.

Rimfire Research

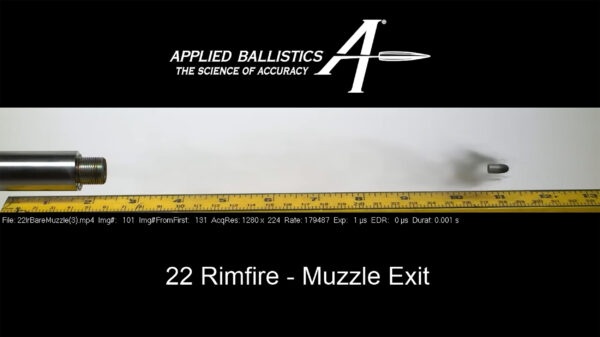

Bryan explained that rimfire is something he’s been wanting to investigate for a long time, particularly due to the very different things he’s heard about it compared to centerfire. 50 and 100 yard rimfire has been around for so long it’s well-understood, but as NRL22 and PRS shooters push the limits of .22 LR, many have more questions than answers.

.22 LR is subsonic, which means it doesn’t have a characterizing stability formula like the Miller Stability Formula for supersonic centerfire. In essence, predicting .22 LR stabilities and trajectories at ranges it wasn’t designed for is uncharted territory. Many wonder why a ballistic solver will kick out very accurate numbers out to 200 yards for .22 LR, then it seemingly becomes less accurate. Some shooters assume it’s a mistake they’re making when it really comes down to the ballistic coefficient. According to Applied Ballistics’ doppler radar research, a .22 LR ballistic coefficient, both G1 and G7, is a poor match for the actual subsonic drag model of the bullet. Though a rimfire bullet’s shape is most similar to G1, the RA4 drag model for air rifle pellets/slugs is actually the closest representation, but it’s not perfect. At the current time, Bryan believes the fix for this will be having well-established doppler radar profiles for every rimfire type and/or a different standard to reference the ballistic coefficient to.

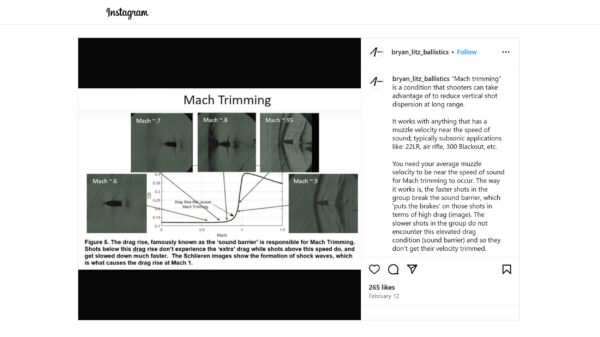

Mach Trimming

Bryan first discovered Mach Trimming when working with SK long range and later observed it with Lapua high-velocity ammunition. Rimfire ammunition with a muzzle velocity near the speed of sound will experience extremely high drag at the sound barrier. It will slow down extremely quickly then proceed to coast at this subsonic speed. This really comes into play with quick, successive shots. Consider firing a string of 10 shots with the average velocity at the speed of sound— half of the shots are above, half are below. Also assume the velocity spread would be 40 fps.

If the faster half of those shots were slowed down as soon as they exited the barrel, immediately losing 10 fps to 20 fps, the extreme spread after 20 or 30 yards is now between 20 and 30 fps. This phenomenon is called Mach trimming and can reduce vertical shot dispersion. There are numerous caveats to this. Temperature not only affects your muzzle velocity, but also moves the speed of sound and affects bullet coatings. While extremely difficult, if you can strike the right balance, you can benefit from approximately half the vertical dispersion you would ordinarily have at that temperature. Another disadvantage to Mach trimming is that windage is most sensitive to high drag. In short, Mach trimming is great for your vertical dispersion but bad for your wind deflection. (Wind deflection is minimized if you stay subsonic from the muzzle to the target.

Mach trimming is to blame for many of the inconsistencies shooters observe at far distances. One day they will have incredibly low vertical dispersion, the next it will be all over the place with the same rifle and ammunition. .22 LR has long been considered unrepeatable, but there has never been an explanation for it, until now. While his research has been focused on .22 LR, this applies to any subsonic ammunition, like .300 Blackout and pistol ammunition. Bryan has written a soon-to-be-published paper on Mach trimming and the nuanced effects of temperature with a complete technical background and much more information.

Group Convergence

Another area of Bryan’s rimfire research is group convergence. This took him a while to consider as he had explored centerfire group convergence (ex. Shooting better groups at 300 yards than 100 yards) and none of his software could model it. To scientifically test this in real-life, he built a shoot-through target and began screening the groups at 100 and printing at 300. Nothing supported group convergence.

He recently began investigating rimfire group convergence because the Lapua Rimfire Performance Center, screening shots at 50 and 100 meters, has observed occasional angularly smaller groups at the further distance. He modeled rimfire launch dynamics in a six-degree-of-freedom-model he built and this time was able to successfully model converging groups. There is still much more to learn about this topic and if convergence is truly beneficial.

Conclusion

Rimfire is an incredibly tricky topic with far more variables than centerfire. To add another issue, the shape of a lead .22 bullet is different in flight because it doesn’t have a jacket to help retain its shape. This prevents you from measuring and comparing the bullet fired and unfired. This conversation with Bryan Litz was absolutely fascinating and I look forward to his future research.

Get the Gear

Looking for more rimfire info? Check out The Science of Accuracy Academy and follow Applied Ballistics on Facebook and Instagram!

If interested in ballistics in general, also consider reading Bryan Litz’s latest book, Modern Advancements in Long Range Shooting Vol. III.

Don’t miss out on Ultimate Reloader updates, make sure you’re subscribed!

Thanks,

Gavin Gear