Deer, whether whitetail, blacktail or mule deer, are not huge animals. A big mature buck is rarely over 300 pounds and most are far smaller. They’re also really not very wide from side to side, have smallish bones and their hide isn’t particularly tough. This begs the question: Why do I hear deer hunters so often talk about needing “knock down power” or “deep penetration” before extolling the virtues of their favorite hard-kicking cartridge?

Disclaimer

Ultimate Reloader LLC / Making with Metal Disclaimer: (by reading this article and/or watching video content you accept these terms). The content on this website (including videos, articles, ammunition reloading data, technical articles, gunsmithing and other information) is for demonstration purposes only. Do not attempt any of the processes or procedures shown or described on this website. All gunsmithing procedures should be carried out by a qualified and licensed gunsmith at their own risk. Do not attempt to repair or modify any firearms based on information on this website. Ultimate Reloader, LLC and Making With Metal can not be held liable for property or personal damage due to viewers/readers of this website performing activities, procedures, techniques, or practices described in whole or part on this website. By accepting these terms, you agree that you alone are solely responsible for your own safety and property as it pertains to activities, procedures, techniques, or practices described in whole or part on this website.

Deer Rifles

What each hunter chooses to hunt with is largely up to him/her, as long as it’s legal to use.

If a hunter chooses to shoot a very powerful hard-kicking rifle for deer, that’s fine, it’s just not typically necessary. Claims of “more killing power” and “quicker kills” are common. Well…it’s awfully hard to beat instant drop and death, which can and has been done with soft-shooters like the .243 Winchester and other smallish rifles. Instant is pretty doggone quick.

The 22’s

My personal experience with 22 centerfires on deer is limited to using a 16” barreled AR-15 with 55 grain soft point Federal .223 ammunition on quite a few injured and/or sick mule deer, some of whom were quite mobile. I don’t consider this hunting, but there was no doubt the little rifle dropped each of them quite quickly.

Some hunters have relied heavily on the .223 and the .223 AI for deer hunting with good success. The .22-250 and the .220 Swift offer even more velocity and are fine for taking deer WITH good bullets.

When selecting 22 caliber bullets for deer hunting, it’s vital to avoid lightly-constructed varmint bullets. These are intended to expand violently on impact and may fail to penetrate, inflicting terrible surface wounds on bigger game without killing them. Conversely, some target bullets are not built to expand at all. These may penetrate without expansion, thereby not producing sufficient damage to quickly incapacitate game.

Note that not all states allow 22 caliber rifles for deer hunting, check the regulations!

The 6mm’s

6mm hunting cartridges aren’t new on the American deer hunting scene. Both the .243 Winchester and the .244 Remington were introduced in the 1950’s. The .244 was later given a faster twist barrel and heavier bullets to become the 6mm Remington. The higher velocity .240 Weatherby also appeared long ago and is a gem. Even as a kid, I was a rifle cartridge and ballistics junkie. Dad rewarded me in 1974 with a brand spanking new Remington 700 in 6mm Remington. That rifle is now my son’s and he has done really well with it, typically sending a 95 – 100 grain bullet at 3,000+ fps. He’s taken mule deer and whitetail with it with no problem.

His first deer with it is worth mentioning. He was 12 years old and could legally take a mule deer doe. We spotted several at about a half mile away and stalked closer. When we got to within 300 yards, we ran out of cover, leaving nothing but 275 yards of grass between us and the deer. He got down into the prone position with the rifle on a bipod and squeezed. The little 95 grain bullet entered the chest and destroyed the lungs before exiting, shattering the off-side fore-leg. The doe dropped instantly and the young man had his first deer. The little 6mm had proven its worth again, and started a new hunting career with the young man.

I like that John continues to honor the little 6mm Remington by using it for deer hunting, though he also hunts with more powerful rifles. These days I also load and shoot the 6mm Creedmoor, using a 108 grain bullet at about 3,000 fps — roughly the same ballistics as a .243 Winchester or 6mm Remington.

I see no reason why the 6mm Creedmoor wouldn’t be at least as effective as either of the older American 6mm’s. With the ability to handle longer, heavier, higher BC bullets, it should prove superior, while being just as easy to shoot.

The Neglected 25’s

America is home to the 25 caliber cartridges and we’ve had quite a variety of them from small 25’s used in lever action rifles to the rompin’ stompin’ .257 Weatherby Magnum. The 25’s made quite a mark on the hunting world but appear to be losing popularity. I believe one reason for this is the adherence to the standard 1:10 twist. This works great with conventional bullets up to 120 grains or so, but can’t stabilize newer, high BC bullets. Only recently have long bullets and fast twist 25 caliber barrels become more commonplace.

The first 25 caliber I met was my grandfather’s .257 Weatherby Magnum. He had a Mauser sporter in .257 Roberts re-chambered by Weatherby’s old southern California shop into the then-new, smoking hot, .257 Weatherby Magnum. I still have that rifle and his original dies which were intended to resize shortened .300 H&H brass to .257 Weatherby. After reading of the amazing results from the various Weatherby magnums and hearing of Grandpa dropping deer as though they were struck by lightning, I approached that rifle with caution. I quickly learned it had very little recoil. The wheels started to turn— perhaps deer hunting didn’t require a big rifle… By the way, the .257 Weatherby Magnum continues to reign as the fastest regular production 25 caliber rifle cartridge, some 70 years later. Newer bullets and newer slow-burning powders have only made it better.

Approximately 20 some years ago, after giving my 6mm Remington to my son, I realized I missed having a light-kicking, flat-shooting deer rifle— so I bought my first .25-06. I went through a couple of them in short order and learned I really liked the cartridge but wanted a more comfortable rifle. About that time, Remington introduced their new 700 CDL configuration: a lighter, trimmer, sporter version of their 700 series. I ordered one without hesitation and after all these years, it’s my optimal open country deer rifle.

I’ve shot mule deer from 20 yards to 400 yards with it. The .25-06 handles it all with aplomb. Crosshairs on target, squeeze. Go tag the muley. Same thing with pronghorn antelope and coyotes. I don’t have a nickname for this rifle, but if I did, “Off Switch” would be a contender. The only time I felt under-gunned with the .25-06 was while hunting mule deer in Wyoming in 2009. My partner and I hadn’t found mule deer down low in sagebrush country so we went up into the mountains and hiked up a remote canyon. Soon we were walking on a trail riddled with grizzly sow and cub tracks. Those 25 caliber, 115 grain Berger VLD hollow points didn’t seem to be quite the best answer to a grizzly problem. Fortunately, the grizzly left the drainage and my partner and I each took a mule deer. He dropped a buck with his .270 and I made an honest 400-yard shot, holding on hair, and dropped a mule deer doe instantly. My .25-06 has gone on to take quite a few more mule deer, a couple of pronghorn antelope and a few unfortunate coyotes, one at 420 yards.

Recently, some newer 25 caliber rifle cartridges have arrived upon the scene. With their fast-twist barrels, they have the potential to rekindle America’s love of the 25 caliber for deer.

The 6.5’s

No one can deny the impact the 6.5 Creedmoor has had on the ammunition and firearms industries. Originating as a target cartridge in 2007, it attracted the interest of hunters and within a few years was seen taking all manner of game at ranges near and far. The 6.5 Creedmoor succeeded in igniting an American interest in 6.5 mm cartridges as a whole. The good old 6.5×55 has been around over 100 years and has an impressive record of taking rather large game. Remington introduced the .260 Remington in 1997, a standardized version of the 6.5-08 wildcat favored by some target shooters. The .260 deserved a better fate, but never developed a fraction of the popularity of the 6.5 Creedmoor. Gavin paired his 6.5 Creedmoor with a 143 grain Hornady ELD-X to take a black bear here in Washington. It accomplished that job just fine.

There are grizzled hunters looking at their battered .264 Winchester Magnums and wondering what the 6.5 Creedmoor craze is all about. They have a point. Their long-barreled, belted magnums can produce amazing velocity with the streamlined 6.5 mm bullets—far better than a Creedmoor will ever reach. The recoil of a .264 Win Mag is also not particularly obnoxious. Even so, I doubt we’ll ever see much of a revival of that wonderful old belted magnum. Perhaps the 6.5 PRC will fill that role? There are other 6.5’s, milder and hotter, but only the 6.5-300 Weatherby is known as having tough recoil. The rest are all easy to shoot and can be effective on game.

The 270’s

An American phenomenon, the .270 Winchester burst upon the scene in 1925 and was popularized by the gun-writers of the day. The amazing Jack O’Connor often shot it in his iconic Winchester Model 70. Detractors included Elmer Keith who described the 270 as a “damned adequate coyote rifle.” This feud continues today as some folks still refuse to consider the .270 or other smaller bore rifles serious deer rifles. Others recognize that the .270 Winchester is a lighter-kicking alternative to the .30-06 and is fully capable of taking most big game on the North American continent. In my opinion, it continues to be a mighty effective deer rifle, shoving a 130 grain bullet at about 3,100 fps. Easy shooting and highly effective, nothing is wrong with the .270 Winchester…unless your name is Roy Weatherby. In 1943, in the midst of WWII, Roy Weatherby unleashed his first belted magnum with those classic double-radius shoulders and high velocity upon the hunting world. Anything the .270 Winchester could do, the .270 Weatherby could do better! All these decades later, the .270 Weatherby remains an ultra-high velocity, game-taking cartridge with modest recoil. It is surprisingly easy to shoot from a sporter weight rifle. Earlier this year Gavin produced an article on his 270 Weatherby Mark V. We’ve been awfully busy since then and haven’t gotten to try some more loads, but that’s on the to-do list.

There have been other .270 cartridges introduced with mixed commercial success including the .270 WSM, 6.8 Western, 6.8 Remington SPC, and the 27 Nosler. Most have failed to make much of an impact on the market, but the 27’s should certainly be considered if searching for a flat-shooting, mild-recoiling deer rifle. Honestly, if I was looking for a .277” diameter deer rifle, I’d probably go totally old school and choose a .270 Winchester Model 70 rifle.

The 7’s

The USA got a rude introduction to the 7x57mm in the Spanish-American War of 1898. Most of our troops were using the .30-40 Krag rifle, and it was far outclassed by the Spanish Mausers in 7×57. Fairly flat trajectory, excellent penetration. and relatively light recoil were attributes which allowed the 750 Spanish defenders of Cuba to inflict roughly 1,400 casualties on the attacking force of 6,600 Americans. We took notice and work on what eventually became the .30-06 commenced.

The British with their vaunted .303’s also had an unpleasant encounter with the 7×57 in the Second Boer War in South Africa, 1899. The 7×57 was clearly superior and left a lasting impression. That early version of the 7×57 used a heavy 173 grain bullet at about 2200 fps and was soon replaced by a 140 grain Spitzer bullet at nearly 2800 fps.

Today the 7×57 can be handloaded to easily exceed the old parameters and remains a fairly flat-shooting, easy-recoiling, effective big game cartridge. The ballistics of the 7×57 are emulated by the newer 7mm-08, a necked down version of the .308 Winchester with the advantage of fitting in a short-action rifle magazine.

The .280 Remington is essentially a .30-06 necked down to .284” and was handicapped from the start because it was loaded to low pressure to accommodate slide action and semi-auto rifles that weren’t as strong as bolt actions. The .280 AI (Ackley Improved) became increasingly popular over the years. A few friends of mine use it and report velocity figures embarrassingly close to those of my 7mm Remington Magnum, while burning less powder and recoiling significantly less. Were I building a new 7mm hunting rifle, I’d likely go with the .280 AI, which has been approved as a SAAMI cartridge, though factory loaded ammo is not commonly available.

In preparation for a Wyoming elk hunt, I turned to the 7mm Remington Magnum over 20 years ago primarily because it recoiled less than the 300 magnum I’d been using and promised similar results on big game. I’d admired the 7mm magnum since the 1970’s when I shot a 7mm Weatherby Magnum and found it really didn’t generate much recoil.

My first hunt with the 7mm Rem Mag was rewarded with a wonderful 6×6 Wyoming bull with a nearly 51” spread! The heavy 175 gr bullet penetrated completely through the bull, wrecking his lungs and the big blood vessels atop the heart. He staggered forward just a few steps then collapsed. Before the hunt, I’d been advised to bring a .300 Win Mag or a .338 Win Mag at a minimum… Hmmm… I was pretty well hooked on the 7mm Remington Magnum at that point. Does it have soft recoil? No, but it’s similar to the .30-06 in my estimation and I’m not the first to say it seems to be about the most rifle that most hunters can shoot well. I’ve turned to it for mule deer and pronghorn antelope. It’s more rifle than needed for those tasks, but it was indeed decisive.

The 30’s

America seems to have an undying love affair with 30 caliber rifle cartridges dating from the introduction of the .30-30 Winchester in the 1890’s. There was an evolution to the .30-40, .30-03, then the .30-06. The .30-30 and the .30-06 remain from those early days, better than ever now. Eventually the .300 Savage appeared, then the .308 Winchester and others. Holland and Holland’s .30 caliber belted magnum was early on the scene and comported itself well in both 1,000 yard match shooting and in the hunting fields. Shooter Ben Comfort pushed the .300 H&H into the minds of shooters with his 1935 victory at Camp Perry. The shooting world climbed towards 30 caliber Magnum worship.

Don’t get me wrong — there is much to admire about the various 300 magnums. American SEAL sniper Chris Kyle used one with impressive results in war. About a zillion hunters have used the .300 Win Mag and the .300 Weatherby Magnum with excellent results afield. I’ve owned and used a .300 Win Mag and respect the cartridge tremendously. The push towards more and more power from a 300 magnum seems to have topped out, for now, with the .30-378 Weatherby. The .300 Remington Ultra Mag is worth mentioning as is the new .300 PRC. None of those three are a particularly light-recoiling round, yet all are often used for mule deer hunting out West. They are indeed grand cartridges, shoving 200+ grain 30 caliber bullets to amazing velocities, but light recoiling and easy to shoot they are not.

Even so, many 30 caliber cartridges do produce lower recoil, excellent accuracy, and great results on game. From personal use, I can highly recommend the .30-30, .308 and .30-06 for deer and other game within their respective limits. What are those limits? I’m not sure. I punched a cow elk through the heart with a 178 grain Hornady from my .30-06 earlier this year at 405 yards.

With today’s bullets and powders, the .30-06 and the .308 are better than ever! Long ago I settled on the 165 grain bullet and a hearty dose of H4350 as being a perfect general purpose hunting load for the .30-06. I’m seeing 2940 fps, sub MOA accuracy and excellent results afield with that combo. I’ve taken elk, mule deer, black bear and pronghorn antelope with it. It’s a full power load, but still easier to shoot than a 300 magnum. The good old .30-30 is a fair bit improved at longer ranges with the revolutionary Hornady FTX bullet as well. The FTX gives it quite an extended range over other more traditional designs. Last year I drew a doe tag for Central/Eastern Washington. I’ve always liked the mild-recoiling .30-30 lever action rifles and saw this as an opportunity to use one. One shot with the 30-30 at about 170 yards resulted in a quick kill with the handloaded 160 grain Hornady FTX.

Larger Caliber, Reasonable Recoil

Some favor the bigger caliber cartridges for deer hunting. Why? Tradition. The desire to poke a “big hole” through game, and likely more. Of these bigger cartridges, I’ve only used the .44 Rem Mag in a revolver and the .45-70 from a Marlin lever action. Both did really well and no bullets were recovered, just venison.

Some hunters just prefer to use a bigger, heavier, larger caliber cartridge. That’s fine —and some of them don’t recoil all that hard. The .338 Federal is under-appreciated and does a fine job on North American game. It’s just a necked up .308 Winchester, as is the .358 Winchester. Both are good. I’ve got a friend who has used the .358 Winchester in a Browning BLR to take at least 20 elk, as well as black bear and mule deer. That rifle’s recoil is a bit snappy, but nothing harsh. Another Montana friend swears by his .338 Federal and uses it regularly to take both deer and elk.

The .35 Remington was introduced in 1906 and has an ardent following. It’s been seen as the .30-30’s bigger brother—a better choice for big bucks, bear, and even moose at shorter ranges. Today’s .360 Buckhammer uses similar ballistics and is built to conform to the laws of several “straight wall cartridge only” states. Neither one recoils harshly in my opinion.

So, what is the .35 Whelen doing in a low-recoil article? Goodness! Since the 1920s, this big brother to the .30-06 is credited with being the answer when a 200 – 220 grain .30-06 bullet isn’t enough. The .35 Whelen can toss a 250 grain bullet at an impressive 2500 – 2600 fps for the intrepid handloader…which is NOT a light-recoiling deer round. However, it has long been handloaded down to some very sedate velocities and recoil levels. A good 225 grain soft point at 2,200 fps isn’t tough to deal with at all and produces fine results on deer as well as bigger game.

The .38-55 and the more modern .375 Winchester are not particularly tough to deal with unless the rifle weight is too light and the recoil pad non-existent. Many hunters have pointed out that those two classic cartridges do exactly what the new .360 Buckhammer does.

Remington’s .44 Magnum is a stubby masterpiece of a revolver cartridge. It produces tremendous recoil in a revolver but isn’t bad at all when chambered in a lever action rifle of reasonable weight. The .44 has the advantage of creating a large entrance wound and often a large exit wound, resulting in a great blood trail. I’ve only taken deer with a .44 revolver and it did a fine job.

Marlin resurrected the ancient .45-70 and modified their lever action 336 rifle to become the 1895 handling the .45-70. That version has its own section in most handloading manuals. If loaded to its full potential, it’s far from an easy kicking rifle. If used with factory level ammunition, or with “trapdoor” level handloads, it’s easy to handle and still pokes a very big hole through game. Those are the bigger than normal deer cartridges I know of, but I’m sure there are more. Leave a comment if you use something larger than 30 caliber for deer.

Bullets

Bullet selection is especially critical with less powerful cartridges. When using 22 or 6mm cartridges there’s the possibility of selecting a bullet intended for varmint shooting or target shooting—either of which can result in disappointment when used on deer. As the cartridge diameter grows, there is less problem with this. Each maker produces bullets intended for deer hunting— those deserve your attention. In particular I like the Barnes TTSX; Berger VLD and Elite Hunter; Hornady FTX, SST, ELD-X, the good old Interlock, and the CX; Sierra ProHunter, GameKing and the newer Tipped GameKing; and the Nosler Ballistic Tip, Accubond and Partition.

If you choose a “harder” bullet, one that is slower to expand, consider choosing a lighter version of it that will be driven at a higher velocity to promote quick expansion. It’s expansion coupled with penetration that results in quick kills and filled tags. I’ve never insisted on a bullet that always exits on deer, instead tending to favor a bullet that inflicts major damage inside the chest cavity. However, I know that many deer hunters prefer a bullet that “makes two holes” encouraging a good blood trail for tracking. Sometimes my deer rifles will do that, but often they don’t. As long as it drops deer quickly, I’m satisfied. That seems to be more a function of placing a good bullet well than about cartridge choice.

Recoil

Recoil plays an important part in cartridge selection. More recoil makes a rifle more difficult to control and places an additional burden upon the shooter. Gavin has built a terrific device for measuring recoil and we’ve used it often at UR.

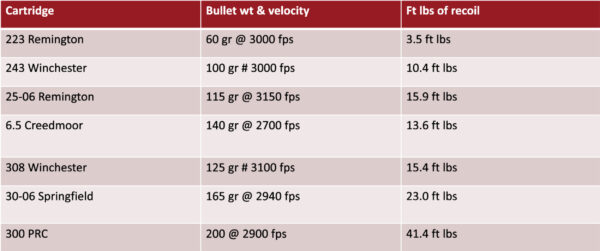

Choosing an arbitrary 8 pounds as a rifle weight, let’s look at some different recoil figures.

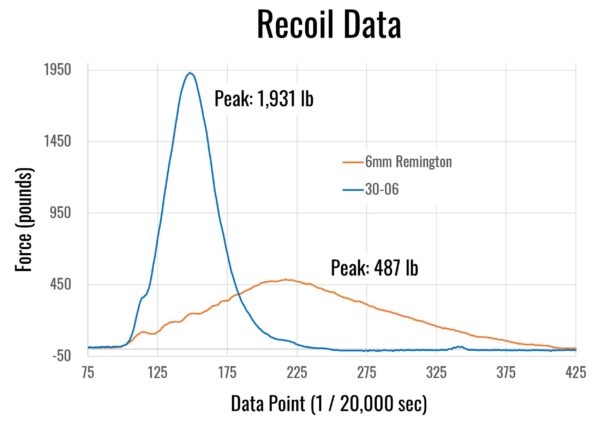

We tested my 6mm Remington and my .30-06 on Ultimate Reloader’s recoil rig. The two rifles have nearly identical weight. The 6mm showed roughly ¼ the peak recoil force of the .30-06.

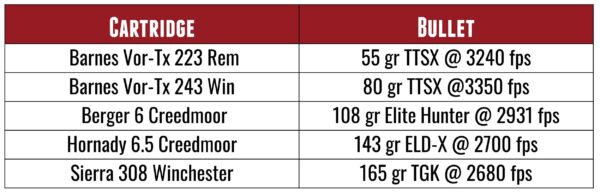

We can select an easier-recoiling rifle, and we can also lessen the recoil of an existing rifle in several ways. As handloaders we can load lower-powered ammunition with less recoil. We can add weight to rifles and also ameliorate the felt recoil by the use of a quality recoil pad. A muzzle brake can make a huge difference in the recoil produced. A suppressor can also help reduce recoil. I picked some commercially available ammunition intended for deer hunting. The selection came from Barnes, Berger, Hornady and Sierra. None of these choices produces substantial recoil in a standard weight hunting rifle.

Conclusion

There are times when using a more powerful rifle makes sense, like when hunting in grizzly country where a rifle may be needed to stop an attacking bear. A friend of mine who has hunted Sitka Blacktail deer on Kodiak island uses his .338 Win Mag on those deer hunts, just because of the potential bear problem.

There’s nothing wrong with using a more powerful cartridge for deer hunting, but for the most part it’s simply not necessary. I enjoy practicing with my hunting rifles, particularly in the months leading up to the deer seasons. An easier-kicking rifle is more conducive to regular training sessions and better shots. I’m sure I’ll continue to do most of my deer hunting with my easy-kicking, venison making .25-06 and other light-recoiling hunting rifles.

Don’t miss out on Ultimate Reloader updates, make sure you’re subscribed!

Thanks,

Guy Miner